163. Treating Eating Disorders: How to Get Help & Get Better feat. David Alperovitz (Program Director of Klarman Eating Disorders Center at McLean Hospital)

listen to this episode:

Tune in and subscribe on your favorite platform: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Stitcher | Google Play | Radio Public | PocketCasts | Overcast | Breaker | Anchor

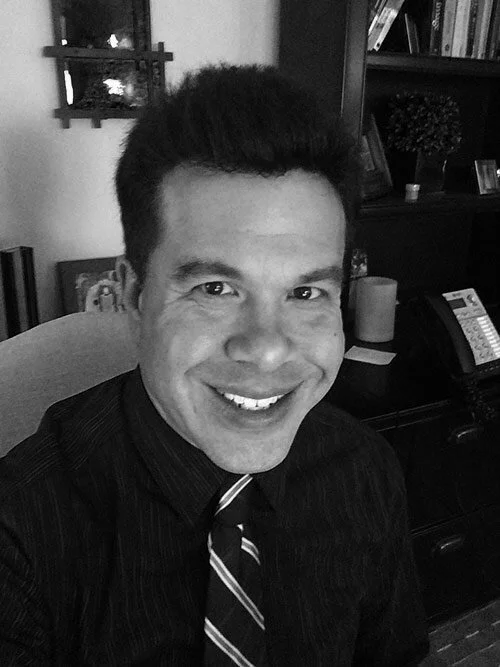

Today's guest is David Alperovitz— an assistant professor of psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and the current program director of the Klarman Eating Disorders Center at McLean Hospital, where he has worked for over 25 years. We discuss his experiences working with people with trauma, eating disorders, and OCD, the role of courage in those being treated for mental health disorders, his work at the Klarman Eating Disorders Center and what the center’s treatment approach looks like, key things people should look for when seeking evidence-based treatment for an eating disorder, things he wishes the general public knew about eating disorders and OCD, what eating disorders have in common with anxiety disorders and OCD, his advice for someone experiencing an eating disorder who is considering reaching out for help, and tips from his work at Klarman that teens can incorporate into their daily lives.

Mentioned In The Episode…

+ Klarman Eating Disorders Center

SHOP GUEST RECOMMENDATIONS: https://amzn.to/3A69GOC

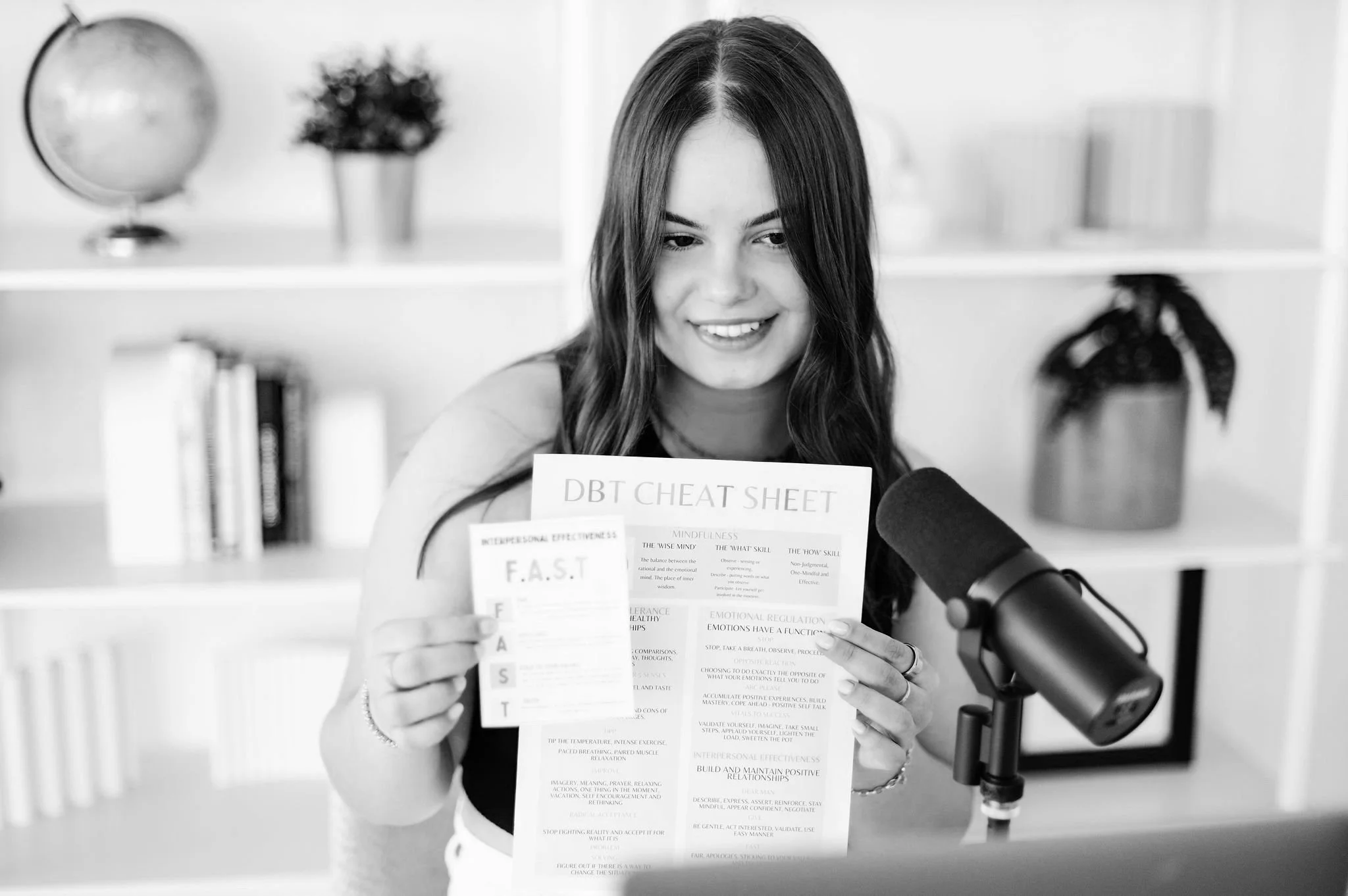

About She Persisted

After a year and a half of intensive treatment for severe depression and anxiety, 20-year-old Sadie recounts her journey by interviewing family members, professionals, and fellow teens to offer self-improvement tips, DBT education, and personal experiences. She Persisted is the reminder that someone else has been there too and your inspiration to live your life worth living.

a note: this is an automated transcription so please ignore any accidental misspellings!

Sadie: [00:00:00] Welcome to She Persisted. I'm your host, Sadie Sutton, a 19 year old from the Bay Area studying psychology at the University of Penn. She Persisted is the Teen Mental Health Podcast made for teenagers by a teen. In each episode, I'll bring you authentic, accessible, and relatable conversations about every aspect of mental wellness.

You can expect evidence-based, teen approved resources, coping skills, including lots of D B T insights and education in. Each piece of content you consume, she persisted, Offers you a safe space to feel validated and understood in your struggle, while encouraging you to take ownership of your journey and build your life worth living.

So let's dive in this week on She persisted.

David: I think it involves a lot of fear, eating disorders.

Although they're not classified in our diagnostic and statistical manual as anxiety disorders, there's so much anxiety that it coexists with eating disorders. And yeah, firstly, they probably could be classified as anxiety disorders. And our instincts with anxiety are [00:01:00] to avoid, right? Out of an adaptive origin.

But with eating, We can't do that. we need sustenance. We need nourishment in order to function

Hello, hello, and welcome back to She Persisted.

I am really excited you're here today because this is one of my favorite episodes. I recorded ever for She Persisted. I think anyone that has struggled with disordered eating or has someone in their life who has struggled with disordered eating should listen to this episode. Today, we have Dr. David Alperovitz on the podcast. He is the current program director of the Klarman Eating Disorder Center at McLean Hospital, which is the Young Adult Adolescent Eating Disorder Treatment Program at McLean. He is also an assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, and he has over 25 years of experience working at McLean. He not only has an extensive history treating eating disorders but he's also worked extensively with patients struggling with OCDs.

I think that all of us listening have either experienced disordered eating or know someone [00:02:00] who has experienced disordered eating. It's something that is extremely prominent in our society, especially with teenage girls, and While we are all familiar with the idea, it's extremely rare that you're able to listen in on a conversation and pick the brain of someone who is working day in and day out with teens in the recovery process, who are finding hope for the first time in years and shifting these behaviors and setting themselves up for success for the rest of their lives with a foundation of healthy habits.

Really doing a 180 with their mental health. I think myself included, we have this perception that it's just about the behavior. It's just about these habits,

it's about the spectrum of, like, under and overeating and all these different behaviors that come into the diagnosis. But I think this conversation really sheds a light on how much goes on underneath the surface. How anxiety and avoidance driven these behaviors are. How closely tied they are to our internal belief systems.

And also how much overlap there was in my own experience in [00:03:00] treatment with building a life worth living and how important that is in eating disorder recovery as well.

So I don't want to go on too long in this introduction because I just want you guys to be able to listen to this conversation because it's so powerful, but if you are looking for hope in your journey, if you're trying to understand someone else's experience, if you just want to have a better understanding, of Eating Disorders, this episode is for you.

And if you enjoyed it, as always, please share with a friend or family member. Post about it on social media. I think this is a conversation that deserves to be heard by so many teens and other individuals out there. And I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Sadie: Thank you so much for joining me today on Sheep Resist Dead. I'm so excited to have you here on the show.

David: Very excited to be here. Thank you for having me.

Sadie: Of course!

So for listeners who have not heard you speak before, I would love to give a little bit of context on your career and the work you've done in the mental health field. You have such a unique perspective And I'd love to hear about your journey and how you ended up [00:04:00] working at McLean.

David: Well, it's not a journey, I think, that anyone would script.

I was a psychology major in college and, and both my parents, my mother and my stepmother Our therapist. So I didn't actually have a whole lot of interest in what they did growing up, kind of went on behind closed doors. They worked at home. But then, as I got into college, I really became more interested in sort of helping others through therapy.

Did some volunteer work, not not in a therapeutic strict sense of therapy, but really working with some adolescents and working in a small community mental health center and just enjoyed it. So I got a job out of college working at a small private psychiatric hospital as a mental health worker.

And it kind of went from there, but it's interesting. Initially, I was scheduled to start the job. It was like a couple of days after graduating from college and work on an adolescent inpatient unit, kind of a general inpatient unit. Yeah. And it was like tumbleweeds. It was closed. It was dark. I was like, what's going on here?

And they said, our census dropped. We had to close the unit over the [00:05:00] weekend. And I'm like, well, I'm here. What, what do you want to do with me? And so they, they kind of put, they didn't really know what to do with me. They put me on what was called the women's unit. which essentially was a trauma and dissociative inpatient unit with adults.

And so literally just by chance, and I just loved it. I just felt affinity for the work and the sort of courage that these women were showing to even just begin to put voice and feeling to what they had experienced. And then there was, I think, a unique Privilege in being a male. And, you know, I think trust was something that was probably in general hard for most of these folks to come by, but even more so with a man, and it was never like the light switch that went on and was on forever.

It was an ongoing challenge. But I love that. And I love the possibility of being a gentle, listening presence that could provide a little bit of a different experience than what they had experienced before in a good way. So that was literally by chance and from there I, I came to McLean and, [00:06:00] and took a similar job as a mental health specialist on, on what was called their trauma and dissociative disorders unit which I continued to love and enjoy, but I became fascinated by a large number of the patients coming in with, with Co occurring eating disorders and really doing a whole lot to help them.

We weren't really set up very well to help but there was a good number. And I was fascinated by, by wanting to learn more. And so after a number of years, I, I kind of. An opening came up at the Klarman Eating Disorder Center, also at McLean. And so I transitioned to a new role very nervous and not really knowing a lot, but eager to learn and very curious.

And I love that too. Yeah. This has been the story of my career. I've really, literally loved everything I've done. And so I came to Klarman I think around, 2010, maybe. I spent about eight years here as a staff psychologist. This is after graduate school, and I worked at [00:07:00] McLean part time through graduate school.

And again, I loved it. I, I, there was a similar sort of. Feeling of courageousness and being able to bear witness to people leaning into things they were really afraid of and sometimes going against their instincts about what they wanted to do, but doing it anyway. And there was this great experience of seeing people literally physically grow and then emotionally come to life.

And kind of getting to know them and really being a part of that was just a unique and very special experience. Yeah. So again, as. Is now a pattern. I noticed that there was a good number of people coming into the climate center with service who also had O C D mm-hmm. , and we actually were doing a little bit more to help them.

But I became fascinated by O C D and I, I, again, was. Very naive and really didn't know a whole lot about cognitive behavioral therapy or ERP It was kind of like a foreign language to me than a little bit of CBT, but it's mostly trained in a psychodynamic Environment and so he was new and I was [00:08:00] interested and I got an opportunity to go to the OCD Institute At McLean.

So after eight years at the Klarman, it's very sad to leave But excited for something new. And I went to the OCDI, and was there for four plus years doing behavioral and ERP therapy, learning about OCD, and absolutely loved that. And again, that similar dynamic of people leaning into, Their fears going against their instincts, showing tremendous courage was incredibly rewarding to be a part of.

I learned as much from them in that experience as they learned from me. And then the opportunity came to come back to Klarman. And I felt even more prepared to come back in the role of the program director, having had all these sort of diverse experiences with trauma and OCD both of which, you know, occur in fairly high numbers with eating disorders, among other things as well.

But it was a, it was a difficult thing to leave the OCD. I was the shortest I'd been anywhere, it was four years, [00:09:00] and I was loving it, but I, it was a good opportunity and, and another place that I thoroughly loved to

come

Sadie: back to. Definitely. One thing that you mentioned in those different areas that you concentrated was the courage that it took for these patients to do the work and also how it Felt counterintuitive and against their instincts.

Can you speak a little bit to that? Why it can feel so foreign to do the work and rewire these thought processes and maybe move in the right direction

David: Yeah, and and it truthfully it's something that You know, as I was learning, I struggled to understand myself. It's a great question, right? Because it's not always intuitive.

And I think from the outside, we can see people struggling with something. And we'll say, well, just do it, you know. Touch the door knob if you feel it's contaminated. Or eat the food if you're worried about it. Just eat it. Very simple. But it's not, right? And, and, it's I think the tendency when we see something that we don't understand is to try to simplify it.

And often that that comes out in a way that becomes very pathologized, right? That it, [00:10:00] it, is shameful. It, it implies something is easy when it isn't, or it's simple when it's complex. And these behaviors were really born out of an adaptive origin. If it's someone who's experienced trauma, and they're avoiding situations because of what they've experienced, That's to protect them.

It's born out of an adaptive experience, right? If someone is, you know, acutely anxious that their mother will die if they don't knock on this table three times, again, they're trying to protect their mother. They're trying to do good. Now, these symptoms aren't serving them in a way that's useful because they don't necessarily need to worry about their mother.

dying or they don't necessarily need to worry about a trauma occurring in every situation that they enter into. The origin of these symptoms makes sense, right? Asking them to do something different, to lean into these fears, to be in a situation with men or other people, to touch the doorknob, to, to eat a fully nourished meal on a regular basis.

Is not a small task. Yeah. Yeah. Take courage. And I think, you know, just understanding the adaptive [00:11:00] origins and, and trying to be curious about what those may be. They're not always evident. It is really, I think a good part of the work and really helps not to apologize what anyone is going through or, or simplify it or, or suggest that it's easy.

Cause it's really quite complex and very.

Sadie: Very hard. Yeah. I think that's such a compassionate way to approach this whole world that a lot of people don't have insight or empathy for, and they want to support someone, but they maybe don't understand it. And so I love that advice, and I think that's very, very helpful for parents and also individuals who have a friend or a family member, whoever it is, that is struggling with these different types of things that we can't always empathize with, or maybe you don't have the lived experience to fully empathize with.

I wanted to ask about the work you're currently doing, continuing along the track with eating disorder treatment, because I found it to be one of the biggest black boxes of the treatment world. I felt like a lot of people that struggle with depression or anxiety or self harm or suicidal ideation or trauma, like, [00:12:00] A lot of those things overlap.

You try similar things, you're all mixed in a group together. Family therapy is thrown in there also. Whereas when you're navigating eating disorder treatment or OCD treatment, it tends to be very unique and a different approach. And a lot of the times it's a different program. So for people that are unfamiliar and maybe they're listening to this episode because it's something that's been brought up in their own treatment journey, or again, they have a family or friend that is potentially going to go to eating disorder treatment.

Can you describe what your guys approach is at Klarman, and also if it's helpful differentiating from other programs? Because, again, like, not all treatment programs are created equal, and you guys have a really incredible approach that you

David: take. Yeah, no, it's you know, I think with both OCD and aging disorders, There there's good reason why they tend to occur in more isolation.

Yeah. That's kind of what interested me in them because I felt like we weren't really doing justice to these other disorders. They really need to be treated in more specialized programs, so to speak. So there's good reason for that. At the same time, there's a [00:13:00] drawback and that I think it creates this myth, and actually probably scares a good number of people from working with these populations because I think.

Incredibly highly specialized and sophisticated. And there is some of that. I don't want to put down, you know, the sort of notion of having expertise in a particular area. That's important. But it also really comes down to some of the good fundamentals of psychotherapy. Being empathic. listening and being curious and meeting people where they're at.

It's really the contextual things of having a supportive surround, in my case at a residential setting, a 24 hour, 7 days a week supportive setting where staff can really help patients day in, day out. with their struggles and their relationships with food, their body, size, weight, whatever it may be, or whatever combination it may be.

That's for, for people that are really struggling, really need it. And that if they have sort of sporadic support, it can undermine their efforts, because they, they may sort of white knuckle it through with the support, and then when they're in more [00:14:00] isolation, revert back to behaviors that, you know, just bring them more.

You know, backwards in a sense or help them to progress into the eating disorder instead of forward into recovery. So at Klarman, yeah, I mean, I, I think it's interesting. We have an eclectic approach. And I think that's by design. It's partly a product of, of the, the diverse staff that we have in terms of their background and training.

But it's also really, I think, speaks to people coming in with, in different places with their eating disorder. And, and needing different things. So, you know, we definitely have a more traditional psychodynamic approach in terms of largely formulating some of the cases and understanding some of the deeper origins of what might be the root causes, if we can identify them in an eating disorder.

But practically speaking, in terms of some of the work, there's a very behavioral element. So we do a lot of CBT and we do some acceptance and commitment therapy. We do some enhanced CBT. It's, it's a mix of many [00:15:00] things. And I, I think it works well. We, we don't have a big enough program where we have separate tracks for various eating disorders, let alone separate tracks for people that come in with co occurring trauma or substance abuse, but we'll work with everyone where they're at, and we will have certain groups that, you know, we have a woman in recovery group, which is a specialized group with people that, struggle with co occurring substance use and, and abuse.

We have a Coping the trauma group. And then we'll also augment their individual therapy with some individual work around whatever it is that they may be struggling. And there may be some individual ERP work. There may be. Some particular individual work around body image or art therapy in addition to the group work that goes on.

And I think that's where we really excel in, in working with people that don't fit neatly into boxes and have symptoms that, you know, may cross different boundaries. And we can try and meet them in a number of different areas at the same time because otherwise it becomes a little bit like whack a mole.

Like, you know, we're doing really well with the [00:16:00] eating disorder, now the OCD's popping up or, Yeah. You know, the intrusive thoughts are popping up or the flashbacks are popping up and we really want to be able to support all of these, these areas as much as we can.

Sadie: One thing that I think is also interesting about this realm of treatment is that it's not generally understood what the evidence based protocol is.

I think people maybe are starting to be like, okay, maybe OCD, you're doing more CBT. I think insomnia and CBT because of all like, the apps and things for that is like starting to be more common. Depression and anxiety, talk therapy, sometimes DBT is thrown in there. But with regards to what the evidence based treatment is for eating disorders, it's not as normalized.

I think like you mentioned, it's probably because a lot of the times a holistic approach is taken and there's not a one size fits all for every patient. But for parents that are listening and are like, teen is struggling, but I'm not even sure where to begin. What do you typically recommend when individuals are looking for care providers?

Are they looking for someone to support with medication [00:17:00] management? Are they looking for a therapist that for sure does CBT and ACT? Like, what are you recommending based on what the current research shows? And I think that also goes for like the level of treatment. I think there's also this belief that you have to be in a hospital setting or you have to be getting medical treatment as well as mental health treatment at the same time.

So what are your thoughts there as far as how you recommend parents and treatment teams approach this?

David: It's another great question and it's actually one of my sort of pet peeves that there is not more evidence based Yeah. that is recommended for eating disorders. You know, it, I think the result of that partly is there's, there's not a lot of money in eating disorder research.

Sadie: Which is so interesting because so many people struggle with disordered eating. Right,

David: and there's, there's a proliferation of eating disorder treatment centers, right? Yeah. There's a lot of them, and I'll go to these conferences, you know, they all have tables, but they're all really, not all, but most of them are really about treatment.

But not, I don't have any research connected with the movements. Some of the more academic sites and [00:18:00] some of the not for profits may have a little bit more research. But even so, it's, personality disorders and eating disorders are two of the lowest funded areas of mental health. So that's part of the problem.

And I think, you know, we, we need to bring more awareness. There's a, a really large scale study that we're participating in now through the Claremont Foundation and the Broad Institute trying to look at the biological risk factors for eating disorders, and it's a huge scale study. It's really just at the outsets.

But my hope is that that will spur more in terms of interest in treatment outcomes. But you're right there. There's not a lot of evidence that with that, you know, sort of is that evidence based treatment? Label, there's a lot of evidence to suggest that treatment works. it's for actors evidence for cbt There's certainly evidence based treatment for family based therapy for younger folks.

Some enhanced cbt for binge eating and bulimia But the evidence is Scarce. So what do I recommend given that backdrop? Two things. You asked two different questions. One [00:19:00] is sort of, you know, in an individual therapy situation. Again, I think there's this myth that the person needs to be an expert in eating disorders.

They need to have some knowledge of eating disorders. But more, more than that, they need to work within a team. And they need to work with a primary care doctor who can monitor labs and levels. They need to work with a good dietitian that can prescribe a meal plan. So there's not this, it's really a team approach and the therapist is not charged with holding all of this.

That's too much and it's, it's beyond their area of expertise. So they need to have some awareness of eating disorders. But first and foremost, they need to be kind. They need to have the capacity to understand what it is like to walk in that daughter, that woman's, that son's, shoes. They don't need to know who they are exactly, but they need to have the capacity to understand what it's like to be them.

That's what I always recommend and working as a team. Is, is critical with eating disorders because they're, they're complex and they have different struggles in different areas and you don't want to spend all your time in [00:20:00] therapy talking about meal planning. There are other things to talk about and that has a good realm with a dietitian, nutritionist.

And then you mentioned that the, the level of care too, that's, that's really important. And there are certain, you know it's, it's difficult with eating disorders because objectively weight is one symptom for anorexia in particular. So that can be a little bit easier in terms of gauging level of care.

But often people can present at pretty low weight. You know, their vital signs may look pretty good actually. And, their labs actually pretty normal. And they're doing really well in school. A lot of, a lot of perfectionism and high functioning eating sort of patient out there. And so it's like, well, what do you do?

What level of care? I don't want to pull someone out of their life. They're kind of doing okay in some realms, but, but the weight is down and what do you do? That's the difficult thing, right? Because all these, sort of evidence that everything is okay are not really good evidence. They could change in a minute.

And yeah. You know, and things could become very dangerous very quickly. So you know, we do look at sort of. Where [00:21:00] people's weight is in terms of their acuity, where their labs are, if they are positive, if they are abnormal, that's a good risk factor that we can, can grab onto, but when they're okay, there's also risk factors that play how quickly have they lost weight, how much are they benching and purging um, what other behaviors are they using, their context of substance use mixed in, are they disinhibited, are they making poor choices, which can very quickly dictate a higher level of care to support some um, I'm always a kind of less is more.

So, you know, unless there's wearing, let's, let's try to disrupt life as little as possible and start with psychotherapy, maybe an IOP program and if those things are not working or they do need more support and that becomes clear, then we can always bump people up in terms of level of

Sadie: care. Absolutely. I think that's so helpful especially for parents who haven't had a kid who struggled in this way before.

They don't have that personal history. I think getting that real bird's eye look is really incredibly helpful. And especially for people that are listening that are going through this [00:22:00] themselves and are like, okay, what can I expect if I go and ask for help? Like, what would those next steps potentially be?

Or if they have a friend or family member, I think understanding what The work looks like is really, really incredibly helpful. I think there's a lot of things that you guys are doing at Klarin that are now becoming more commonplace, that haven't necessarily trickled down to the general population, whether it's how you approach eating disorders, how you understand them like that.

You're really focusing on what the cause might be. And yes, you're focusing on the behaviors, but that's just almost like a presentation of the root issue. What are some things that you wish the general public knew about eating disorders and O C D?

David: You know, I think coming back to a little bit of what I was talking about earlier, I think there's often a sort of frustration when people don't know something, and particularly when it's someone you love, there can be a frustration that comes out in a pathologizing way, and it blinds people from really seeing more and understanding more.

You know, I wish people would understand. No, this isn't simple and simple, doing [00:23:00] something different. And no, it's not all about one thing. And that's very important for parents to know, see too many parents that feel like, oh, this is one conversation I had when she was seven. And ever since then, and, and maybe that was an impactful conversation.

Okay. But that's not, yeah. The root cause of this, right? And I think, you know, that's the tendency. Again, when we don't have a lot of information or don't understand something, is to try to want to simplify it. It's because of this, or if you just did this, it would be better. And it's, it's so much more complex.

I mean, if it was that simple, that would be awesome. I mean, I mean, Yeah. Building that I'm in right now wouldn't exist, but that would be awesome, something else to do, but unfortunately it is so complex and it is such hard work and it's counterintuitive, right? Because I think it involves a lot of fear, eating disorders.

Although they're not classified in our diagnostic and statistical manual as anxiety disorders, there's so much anxiety that it coexists with eating disorders. And yeah, firstly, they probably could be classified as anxiety disorders. And our instincts [00:24:00] with anxiety are to avoid, right? Out of an adaptive origin.

But with eating, We can't do that. We need to, we need sustenance. We need nourishment in order to function. So, you know, I, I think that's my primary wish that people would be able to have a better grasp and understanding and be more mindful of the complexities that, occur at both, both in the presentation and the origin of eating disorders.

Sadie: Yeah, so interesting. I'd also love to hear your thoughts on kind of like the parallels between the populations that have OCD and also have eating disorders because like you mentioned, they can be very similar. They've both almost been on the sidelines with regards to what types of treatment are being studied and also how they're treated much more independently.

But what do you see is very common between those two specific populations and especially with regard to treatment?

David: But clearly the most common parallel is avoidance. Yeah,

Sadie: yeah.

David: With OCD it could be avoidance [00:25:00] harm, it could be avoidance of contamination. With, with eating disorders, it's avoidance in some way of food or compensatory behaviors to manage the relationship with food.

And we see that in OCD, through compensatory behaviors to manage manage anxiety. So if I'm going to do something, I'm going to take a ritual. I'm going to say a mantra. I'm going to count a certain number. I'm going to retrace my, whatever it may be to, to try to make it okay. And, you know, I think that again is clearly well intended, but it actually only further serves to fuel the fire of anxiety.

There must be good reason why I'm doing all these quirky behaviors or why I'm avoiding for, there must be good reasons. Because my fears will come true. My mom will die if I do this. I'll become so big that people won't recognize me. And, and, you know, the more we engage in those behaviors, the more prudence we give to the ultimate fear.

So it's sort of this, spiral by engaging in behaviors, [00:26:00] we're fueling the anxiety that drives more behaviors. Yeah, so there's definitely some very clear parallels in, in the symptoms and then in the treatment as well. I mean, if you, If you think of you know, literally sitting down to have a meal or a snack, in many ways that that's an exposure, right?

And we're exposing someone to something that at best they have a lot of ambivalence about, at worst they have a lot of fear. And we're asking them to lean in to bear that fear. To have that meal or or that snack and complete it and then sit with the discomfort that comes without using Compensatory behaviors without urging without exercising Without any idiosyncratic ritual, whatever it might be Really just sit with that discomfort and see what happens for better or for worse.

And there's some real parallels with ERP and OCD in that room. Sitting with

Sadie: uncertainty. Yeah. I think that's so interesting because it really, the more you talk about what treatment looks like in these larger philosophies that are guiding eating [00:27:00] disorder treatment, the more similar it sounds to treatment for depression or anxiety.

And it's a lot of this avoidance and going towards what's uncomfortable, whether it's being vulnerable or internal belief systems or these behaviors that have been avoided for so long. Like there's a lot of parallels and a lot of those core emotions and experiences are really similar, which I think is so interesting.

If there is anyone listening that has not asked for help with regard to either disordered eating behaviors or thoughts that they've been having and they, after this conversation, are feeling more motivated and hopeful to ask for help, What would your advice be to someone that's at the beginning of their journey with either recovery or getting support or diving into the deep mental work that we've talked a lot about in this episode?

What would you say to that person?

David: Reach out and ask for help. I, I think there is a, a, an element of shame and secrecy that many folks with eating disorders have, which leads to people being much more alone with what they're struggling with. Reaching out and asking for help. [00:28:00] It's not a small step.

But I think I have a real believer that recovery from anything Rarely occurs in isolation. It almost always occurs in the context of relationships whether it's a therapeutic relationship Whether it's a good friend reach out to someone and that's the starting point you know people can gauge who that person might be in terms of would they trust more?

But it's a big deal to reach out with uncertainty and ask for help, even to acknowledge that something is going on. And I think sometimes people get So caught in what they think is an adaptive behavior, and they think it's really sort of striving to sort of keep these fears at bay, that it becomes what they know.

And sometimes they lose the perspective that there's anything wrong to begin with. It may be that someone else has brought up a concern, even through their secretive nature that resonated. And if there is an inkling that, you know, maybe there's some struggling in, in my relationship with my body or with food or my size or shape, reach out, talk about it with someone.

That, that first step, and it doesn't need [00:29:00] to be an expert in eating disorders. It needs to be someone who's curious and understanding and nice. And then you can go from there and trying to find the right match for what, but, but. Take that first step with courage and pride too, because it's, you know, I always think, there's also the stigma around asking for help more generally.

And fortunately, there's been a lot more information that's aimed at helping people reach out and to try to reduce stigmatization. But I think about that, like, you know, that association that it's weak to ask for help and further stigmatizes people with mental illness and isolates them. And we all have stuff, right?

And I think about My children. And the biggest thing I would want, like, if they were struggling with something, I want them to reach out. I don't want them to be alone with it. Yeah. That's a strength, right? And, and so really sort of turning that on heels. So being even prideful in, in being courageous and asking for help.

That's a strength. It's not easy.

Sadie: No, I always remember that as being the most challenging part was truly accepting that like, okay, maybe I don't have [00:30:00] everything together Maybe I'm not okay. And maybe I do need help and it's so scary because you can't take it back and then be like We know I actually I'm okay.

Let's just continue life as it was before so it is really overwhelming But I loved how you framed that as almost like inexplicable Exposure hierarchy to asking for help. Like ask and practice the vulnerability with someone you know is gonna respond well and be really compassionate. And then you go the next step and like actually get support from a trusted adult or a pediatrician or whoever it is that you're gonna talk to next.

So I think that's some incredible advice. The last thing that I wanted to ask you is if there are one to two things you guys implement at Klarman that you think young adults could really benefit from having in their daily lives, whether it's an element of routine, maybe continuing the education around how mental health works, asking for help like we just talked about, what are some things that you wish all teens did?

David: So I think the other element, if I was to describe a philosophical approach at Claremont, you know, certainly there's the nourishment, the, the treatment, the therapy, [00:31:00] the groups, all that really important stuff, right. And kind of like our bread and butter, no pun intended, but the other aspect of what we do is really helping people re engage with meaningful life, right.

I don't think that the The nourishment and therapy is a prerequisite for that. They're on equal footing. They're equally important. And you don't need to be nourished to begin to re engage. Maybe at very, very acute levels you need some re nourishment, just to move around and have energy. But beyond that, you don't need to be fully nourished to begin to re engage in life and meaningful activities.

It's equally, if not more important than the other stuff, the therapy. And it gives rationale for doing all this hard work. Why am I doing this stuff that's counterintuitive? It's really hard, it's, it's, it's, you know, grappling with these fears and uncertainty. Why am I doing it? Because I want to get back to playing the violin.

And I can do that at the same time. I can begin to do that at the same time. So the connection between meaningful life and [00:32:00] treatment, and it's, granted, it's, honestly, it's a little hard to integrate those things in a residential setting, because people are somewhat removed from their life. But the more we can do that, the more we can plan for that.

the better. So it's not a like, I got to be all better to do this being better is engaging in these things at the same time. That's the first and foremost thing. And I don't think that's specific to eating disorders, by the way, much more universal, but it gives a really strong rationale and needed rationale to do something that feels hard and sometimes really goes against all of your, your, your basic instincts.

Sadie: Yeah, for what it's worth, I do, I don't know exactly what you guys do with your schedule, but I know at Therese, they also did the same thing with like trying to integrate positive activities and not have it all just be treatment and therapy and I, all the time, I'm like, yeah, we went and we did our ice cream nights, we picked where we were getting our pizza from, we went and saw movies, and so those positive experiences are definitely very impactful and it was like things that I wouldn't have even done at home.

It's like we went to the, like, c Natural history museum or like something random like that and saw [00:33:00] the human body exhibit and so it's almost like that inner child work of like doing these fun things and wandering around and It's definitely really incredible And I think like you mentioned really helpful to have those building blocks and building that life worth living To pull some DVT in but I am so glad we got to have this conversation.

Thank you so so much for being here

David: Well, thank you, Sadie. It's a real

Sadie: privilege. For listeners that would like to continue to learn about Klarman or McLean Hospital, or even your background, where can they find all that information?

David: McLean website there's a Klarman eating disorder page and people can reach out to me directly as well.

I'm, I'm on there and always happy to talk with people. It's one of my pet peeves and people don't get back or leave a message or an email. I do always within 24 hours. So anyway, please reach out.

Sadie: Amazing. I'll put all that in the show notes and thank you again.

David: Okay. Thank you, Sadie. I

Sadie: appreciate it. Of course.

Thank you so much for listening to this week's episode of she persisted. If you enjoyed, make sure to share with a friend or family member, [00:34:00] it really helps out the podcast. And if you haven't already leave a review on apple podcasts or Spotify, you can also make sure to follow along at actually persisted podcast on both Instagram and Tik TOK, and check out all the bonus resources, content and information on my website.

She persisted podcast.com. Thanks for supporting. Keep persisting and I'll see you next week.

© 2020 She Persisted LLC. This podcast is copyrighted subject matter owned by She Persisted LLC and She Persisted LLC reserves all rights in and to the podcast. Any use without She Persisted LLC’s express prior written consent is prohibited.